After examining essential food-related Scriptures in their original languages and greater contexts, it becomes apparent that many Bible texts have been interpreted and translated incorrectly—with a strong dispensational and unkosher bias. Furthermore, it is evident that the relationship between Bible misinterpretation and mistranslation is a vicious circle, where misinterpretation prompts mistranslation, which in turn only feeds more misinterpretation.

Translation Errors—Origins and Implications

For obvious reasons, the quality of a Bible translation is always limited by the quality of a Bible interpretation; but conversely, the validity of a Bible interpretation might be independent of a Bible translation. In other words, things such as human inference, preconceived notions, and finite knowledge can all influence the interpretation of Bible texts, potentially compromising the meaning irrespective of manuscript vintage or language. For example, the understanding of contexts, ancient cultures, history, geography, and even science might all contribute to the meaning of a chapter, verse, or a given word. Consequently, it is to be expected that errors in interpretation might either precede or succeed Bible translation errors.

However, apart from the factors potentially contributing to misinterpretation as described above, translation errors may also stem from an imperfect understanding of ancient languages. In fact, translators repeatedly confess to limited knowledge of the ancient languages, even candidly admitting uncertainty within the footnotes of English Bibles. These cases, however, fail to capture the cases where the translator—even with the best of intentions—had the wrong conviction from the beginning. Moreover, it is also safe to say that no translator will have a perfect understanding of the original and divinely inspired messages; as a result, the accuracy of all Bible translations is further compromised.

Needless to say, even the most diligent English Bible readers can easily fall victim to errors in translation, especially if they are fully dependent on a single Bible translation. As readers try to interpret the English texts through the eyes of translators, they are left vulnerable to assumptions and conjecture far more than they may realize. In effect, English readers are ultimately forced to try to overcome problems of ignorance by ingesting imperfect information as imparted into their Bible translations—not knowing where or to what extent their study might be prejudiced by a translator’s initial assumptions or influenced by a lack of knowledge. Without divine intervention or diligent examination, translation errors are hard for an English-only reader to identify; they are almost certain to balloon into colossal zeppelins of misinterpretation. Such is the case with translations and interpretations related to dispensational dining doctrines.

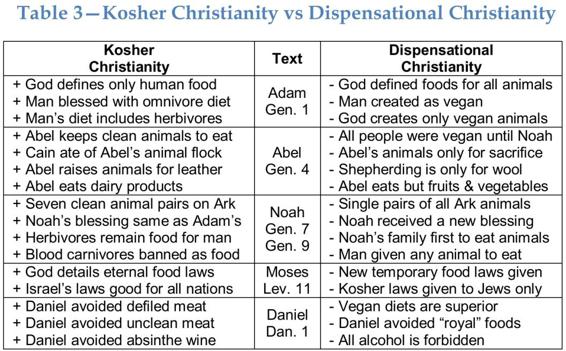

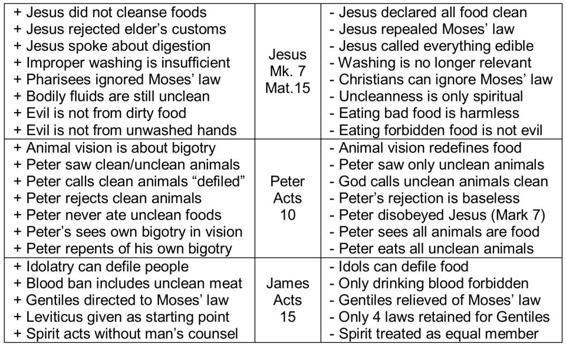

Tables of Interpretation

To help illustrate how presumptive dispensational misinterpretations have produced mistranslations, which in turn have contributed to even greater misinterpretations, Table 3 below includes a summary of points discussed in earlier chapters, contrasting true forms (+) of kosher Christianity against false (-) dispensational food related doctrines. Although Table 3 does not differentiate between errors of interpretation and errors of translation, the summary of accounts below will nevertheless help illustrate how just a few minor and unkosher mistranslations, like those of Genesis 1 and Mark 7, can influence the interpretation and thought progression throughout the entire Bible narrative.

Although food-related comments in 1 Timothy 4 and Colossians 2 were not addressed in prior chapters, the contrasting kosher and dispensational views of these passages are briefly contrasted in the table above, where the same principles apply to interpretation as in earlier New Testament texts.

Translation Dispensations

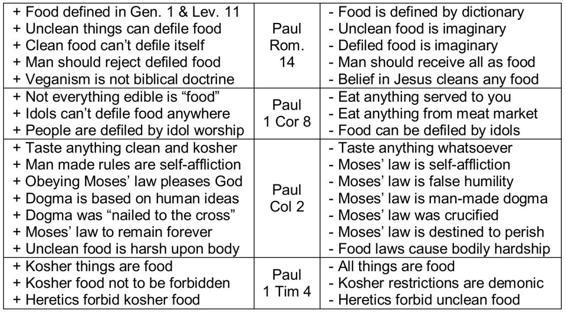

As demonstrated in the table above, several minor misinterpretations and mistranslations have a permeating impact on the Bible’s overall message. The kosher views are consistent with a god that says, “I change not”; the dispensational views leave mankind befuddled with respect to standards of morality and food. Generations holding unkosher views, not being anchored in absolute distinctions between right and wrong, are forced to wrestle with varied dining instructions and dispensations, taking a host of confused people from extreme vegan to unlimited smorgasbord diets.

Figure 2 below illustrates and compares the kosher views to the dispensations assumed by proponents of unkosher views, in order to demonstrate the unreliability of dispensational dining doctrines. Fickle dispensational tendencies are made evident in many translations and traditional interpretations.

Figure 2—Proposed Dietary Dispensations

As the dispensational confusion mounts throughout the Bible narrative, it becomes clear that even the early Genesis mistranslations and misinterpretations presented herein cannot be dismissed as merely theoretical, historical, or even trivial in nature.

It is ultimately the interpretations and the translations of New Testament texts that are likely to have the greatest bearing on a Christian’s everyday life. After all, when Christians are presented with Yeshua’ testimony and identity, they are likely to accept his words as authoritative—some even believing his words were recorded to supersede other Bible texts. Thus, Christians look to New Testament texts for moral reasoning and direction, believing that Yeshua’ words are of greater significance than—and sometimes even contrary to—other Bible texts.

Regrettably, people forget that English was not Yeshua’ native tongue, not realizing that what they believe to be Yeshua’ words are, in fact, mere English translations of the original New Testament texts. From these bad English renderings, Christians presume that Yeshua granted them permission to renounce all food laws, which were otherwise in effect up until his incarnation, crucifixion, or ascension. As a result, mistranslations of Mark 7 have become more than a wayward point of origin; they have become the broken compass by which all Bible food doctrines are oriented. These mistranslations may be likened to an offset rudder that has been used to set the course of titanic dining doctrines whereby the entire crew arrives at the wrong destination, along with an unclean breakfast menu.

Tables of Translation

Given the New International Version’s growing popularity and influence within Christian theology today, it was fitting to exhibit the translation’s dispensational bias present in Mark 7 as well as in the other verses. However, EAT LIKE JESUS should by no means be construed as a malicious assault on one particular Bible translation.181 After all, the dispensational theology that debases the NIV can hardly be attributed to a small multidenominational translation committee deliberating on a handful of verses. In fact, many of the NIV’s dispensational slants are anything but original, as dispensational dogma and anti-kosher worldviews have been prevalent in Christianity and Bible versions for generations prior to the NIV’s inception.

But what about these other English Bible translations? How do they interpret Yeshua’ precedent-setting Mark 7 dining revelations? Do they also propose that “Yeshua declared all foods clean”? Do they suggest that every kind of animal was to be considered “clean” food? Do they assert that food can no longer be made dirty if handled in an unhygienic fashion? Do they describe the caustic purification caused by the human digestion process—whereby foods are “cleansed” and “purged” as they pass through and are expelled from the body?

In response to these questions, English renderings of Mark 7:19 from over forty of the most popular and respected Bible translations182 have been included in tables below for purposes of comparison and consideration. Apart from obvious dispensational biases and overtones, it would appear that differences in translation are defined by the following variances:

- Quotation mark placement – Based on Greek text punctuation, different translations interpret differing endpoints of Yeshua’ words in verse 19.

- Commentary – Based on Greek text punctuation and endpoints of Yeshua’ words, some translations assume that concluding words are gospel writers’ commentary.

- Interjection / substitution – Most translations employ words dissimilar from the original Greek text to help substantiate views on punctuation and commentary.

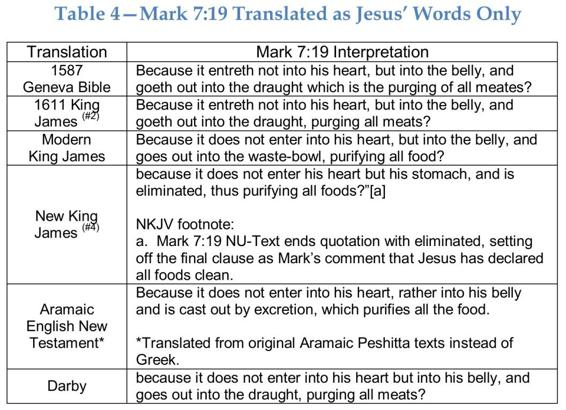

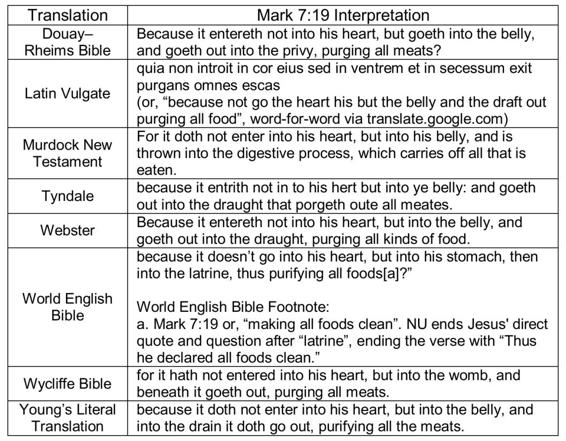

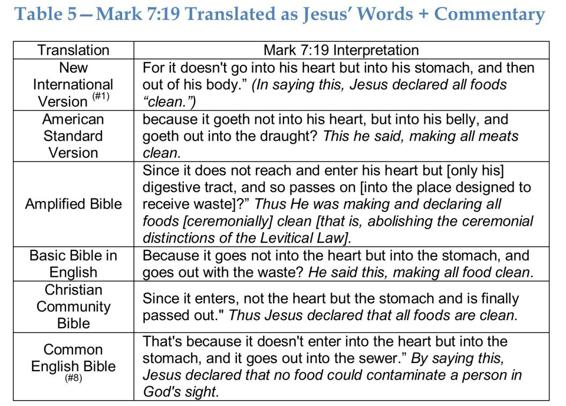

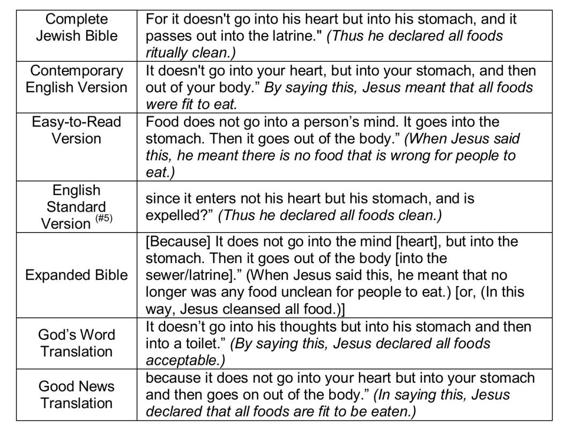

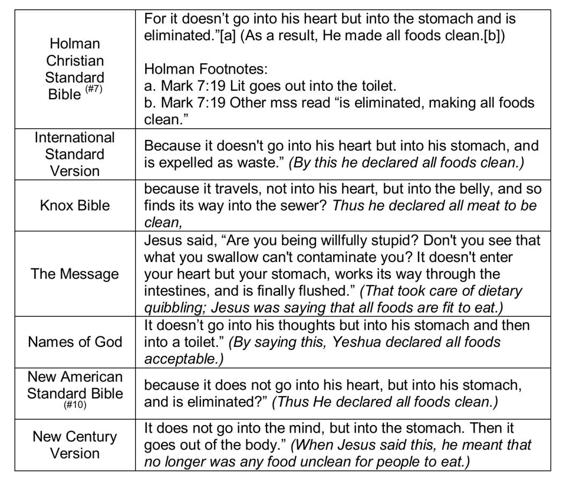

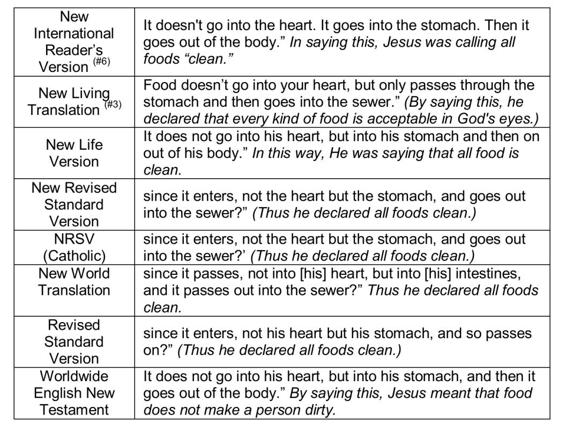

Given such variation, popular English Bible translations have been grouped into two different sets of tables below—one that assumes the entirety of the Mark 7:19 Greek text (see chapter 1 for interlinear presentation) should be interpreted as Yeshua’ words without commentary (Table 4), and the other (Table 5) that assumes the four concluding Greek words of Mark 7:19 are to be rendered as gospel author commentary on Yeshua’ preceding statement.

Per the examples presented in Table 4 above, which are based on inferring all words from Mark 7:19 to be from Yeshua, the majority of the fourteen interpretations translate the Greek verb καθαρίζω (katharizō)183 as “purging,” which is best representative of the context discussing the human digestive process. Moreover, the amount of creative addenda in Table 4 is kept to a minimum, with an average of four English words to replace the four words from the original Greek.

Unfortunately, the Table 4 translations above are a far cry from the majority of translations included in Table 5, which assume that Yeshua finished speaking early, and that the remaining four words of the original Mark 7:19 Greek verse are attributed to Mark’s commentary, where he was annotating the Gospel text.

Translations for Every Appetite

As the 42 English translations tabulated in Tables 4 and 5 above are compared with original Greek texts as included in chapter 1, it becomes evident that all versions that interpret the last four words of the Mark 7:19 verse (e.g. “purging all the meats”) as gospel author commentary (namely the latter 66.6%, as cited in Table 5) are translated with a strong dispensational slant and unclean bias. Moreover, most of these Table 5 translations also seem to interject a sizeable amount of translator commentary on what is assumed to be Mark’s commentary. In fact, translations in Table 5 use an average of ten English words to replace the four words from the original Greek—compared to a humble average of four English words per the translations presented in Table 4, where all words are assumed to be a word-for-word continuation of Yeshua’ teaching.

Moreover, as Table 5 translations populate the conclusion of Mark 7:19 with superfluous verbs, subjects, objects, and adjectives, the texts begin to assume a host of different meanings. Rather than having the digestive tract as the subject performing a function like “cleansing” or “purging,” as the lone Greek καθαρίζω (katharizō)184 action verb should imply, many Table 5 translations transform the verb into an adjective, adding it to the end of the verse, and using it to describe the “food” subsequent to the digestion. Also, in place of the “cleansing” verb, most of the Table 5 translations insert the verb “declared” or “made” in its place, along with “Yeshua” as the subject of conversation. Even though “Yeshua declared” does not appear in the original Greek, these two words are nevertheless routinely added within these creative Table 5 interpretations and translations, implying that Mark was invoking Yeshua’ authority or power to redefine or transform all foods to be “clean,” as he commented on Yeshua’ earlier words—supposedly clarifying what Yeshua really intended to convey.

Further implying that Yeshua was involved in a food conversion process of some sort, most translations go so far as to describe all “food” as “clean,” “pure,” “acceptable,” “fitting,” morally neutral, or even edible—forgetting that earlier in the verse, Yeshua was concluding his description of a bodily waste handling process, alluding to the latrine or the process of expelling unclean human defecation. Some translations insert weaker verbs, such as “meant,” “said,” or “called,” to imply a more reason-oriented interpretation, suggesting that Yeshua was merely using his special insight, superior intellect, or power of observation to reclassify foods contrary to Moses.

Still other translations are far more ambitious and original, boldly inserting the verb “abolishing” in conjunction with “ceremony,” “ritual,” or “Levitical Torah”—even though the original Greek makes no such references whatsoever! In accordance with the Table 5 texts illustrated in tables above, it is clear that the translations read more like doctrinal statements, proving that there are indeed translations to appease all appetites, be they theological or culinary. Some translations appear to be nothing less than novel attempts to avoid copyright infringement or attain a unique status for the sake of copyright claim, in which the final meaning of the translation is of secondary importance.

Translations Reconsidered and Pursued

While this book is hardly meant to serve as an endorsement for antiquated English translations, as an English Bible buyer’s guide, or as a comprehensive critique of Bible translations, it is nevertheless intended to stimulate readers into reconsidering the validity of translations that would otherwise be accepted at face value, or as divinely inspired. Hopefully, at a minimum, this book will inspire readers to question the numerous assumptions and interpretations on which their English translations are based—assumptions which in turn have formulated their traditions and doctrines. For example, what if English Bible translations pertaining to eternal salvation doctrines are as adulterated as simple dining doctrines? Clearly, the translations and interpretations of others are instrumental in shaping knowledge, beliefs, and faith—perhaps far more than most people ever thought possible!

Fortunately, many Bible truths are able to rise above even the worst of translations, even though translation problems may be numerous and blatant. For this very reason, Christians from around the world have expended a great deal of time and effort in order to obtain the best Bible translation available in their native tongue, benefiting greatly from Bible translations. Moreover, over the centuries some have even risked life and limb to translate, to acquire, or to even read the Bible in English.

Today however, after literally hundreds of different English translations have been penned or typeset by an equally vast number of individuals and religious organizations, many people are presented with a very different problem—they want to know which English version to read! They want an accurate translation, one which they can trust as divinely inspired. They want an unbiased translation, free of religious dogma and untainted by political agendas, one that conveys divine authority and instructions without partiality. They want a package that captures the essence of the ancient culture and the spirit of the original text. They want to know what the Bible actually says—not what somebody else thinks it means. And finally, they want it at the snap of a finger, or in today’s terms, at the click of a mouse.

Translation Complications

Of course, even where scholars’ intentions are completely noble, Bible translation is a challenging endeavor often wrought with controversy. At best, translation is an imperfect art complicated by the asymmetrical mechanics of two unique languages; it is anything but an absolute and objective science. In converting a message from one language into another, there is simply no assurance that all ideas, social norms, idiomatic expressions, slang, or even words can be directly transmitted in a like-for-like manner or on a word-for-word basis. So not surprisingly, it is inevitable that translations will take on different words and even different meanings as people of differing perspectives wrestle with various linguistic idiosyncrasies and cultural barriers.

Obviously, individual perspective is guaranteed to further influence and complicate translations. As proposed by the famous Indian parable, a blind man below the head of an elephant might describe a snake like trunk, whereas a blind man surveying a leg might compare the elephant to a tree. Although neither man is incorrect in his perspective, neither man is completely correct either, as neither man can perceive or describe the entire animal. As aptly and eloquently concluded by American poet John Godfrey Saxe,

So oft in theologic wars,

The disputants, I ween,

Rail on in utter ignorance

Of what each other mean,

And prate about an Elephant

Not one of them has seen!185

Bible translation could be likened to ”The Blindmen and the Elephant” poem, as two different individuals might interpret and translate a single verse differently without being incorrect, each expressing a part of a greater truth beyond their own limited perception. Furthermore, personal experiences, passions, aptitudes, and knowledge bases will contribute to differing individual perspectives, thereby influencing how one translator will interpret or prioritize key words or phrases relative to another translator. Where translations are made by more than one individual, multiple interpretations might be blended together in order to create a more complete description. However, such compromises can also produce odd and incompatible heterogeneous amalgamations. Doing justice to neither viewpoint, thinking that their eyes have been opened, what they envision together might easily be mistaken for a snake perched in a tree!

Translation Arguments

Because believers intuitively understand that Bible translation quality is of paramount importance, they zealously guard their preferred English rendition as God’s Word with great passion and even prejudice—often committing to a single translation. In some cases, people may acquire a strong allegiance to a given version simply as a result of personal familiarity and time in study. Others will confine themselves to a particular translation because of third party endorsement, as directed by a parent, pastor, respected teacher, or religious institution. Some prefer to hold fast to their Bible translation as a matter of tradition, reserving a special place in their hearts for texts that sound more established, timeless, or poetic. Still others prefer a contemporary English translation, assuming that translation into the vernacular will maximize their comprehension as a reader; some also assume that new translations represent the summation or accumulation of knowledge, and that the end result is therefore of the best possible scholarship. Finally, there are those who dogmatically believe that their translation was divinely inspired, protected from any possible error in human interpretation, perhaps because the thought of Elohim depriving them of a perfect translation within their own tongue is an idea too abhorrent to accept.

Unfortunately, where strong loyalties are present, great arguments are sure to follow, contributing in turn to battles and factions, many of which divide congregations. These congregations are often comprised of members individually oblivious to the variants in English translation, and equally unaware of what the original language conveys. It is as disconcerting as it is ironic that such caustic fruit should be the end result of hundreds of English Bible translation attempts.

Given this trend toward argument and division, perhaps it is time to reconsider asking “which Bible version is best?”, reverting back to a different question of greater importance, “should the Bible have ever been translated at all?”

Translation Degradation

While questioning the prudence of Bible translation might initially sound absurd and even hostile to Yeshua’ “go ye therefore” Great Commission, it is of some significance that the Bible itself never once instructed its audience to make written translations of its content into other languages.186 In fact, both Old and New Testament texts seem to discourage the practice of creating written translations altogether, given that the translation process inherently introduces all sorts of additions, subtractions, and amendments to the original texts, just as the English quotes at the opening of this chapter discourage.187

Translation of Bible texts into any language ultimately requires compromise; amendments, shortages, and surpluses of all sorts—regardless of method or destination language—are required for translation. Even in cases where a direct word-for-word translation is attempted, such translation runs the risk of not conveying complete ideas because languages differ in syntaxes, logical construction, and vocabularies. In comparison, thought-for-thought or paraphrase translations are hardly without liabilities of their own, for they require the changing of words and omission of essential details. Furthermore, every language has its own set of rules and quirks; things like idioms, metaphors, synonyms, homonyms, rhyme, cultural allusions, preposition usage, and wordplay are not readily captured in translation, yet each contribute uniquely to the meaning of a verse. Because the ancient Scriptures are replete with such intricacies, it is logical to conclude that any translation of the original will result in some level of degradation of meaning or a loss of information, regardless of translation method or diligence on the part of the translator. In fact, it would be absurd to propose anything to the contrary. A perfect translation is like a square circle, or like a kosher lobster dinner; it is a logical fallacy.

Translation Objections

While proposing to apply the aforementioned “don’t add to” and “don’t subtract from” commandments to the tradition of Bible translation may sound radical and unwarranted—even heretical among evangelical circles and Bible societies—there are actually precedents established in biblical texts that seem to oppose written translation of the Scriptures. For example, referring to the original Hebrew Scriptures, Yeshua himself insisted that all of the “jots and tittles” would remain relevant and in effect until “heaven and earth disappeared.”188 In this statement, Yeshua was referring to the smallest letters, decorative markings, and textual anomalies of the Hebrew text, which are uniquely added to select sections of the Scriptures, conveying hints and deeper meanings.189 Obviously, translators have failed to capture such jots or tittles throughout all of the hundreds of English Bible versions created to date, even though Yeshua spoke plainly of the Hebrew precision and deeper meanings embedded within the original texts.

Yeshua was not unique in this ‘revert to the original language’ thinking. The Jerusalem council of Acts was rightfully compelled to refer the new Gentile believers to the synagogues on the Sabbath, where they could hear Scripture read in the original language.190 Likewise, as a great prophet and priest, Ezra grieved as the exiles returned from pagan Babylon, specifically because they were speaking foreign languages and had become estranged from their native Hebrew tongue. Surely, this account suggests that Ezra did not want to translate the Bible into the language of Ashdod or other foreign tongues; instead, Ezra wanted the exiles returning to Israel to return also to the original language of the Bible.191 As priest and prophet, Ezra wanted the people to see things clearly, and to see for themselves. He did not want the restored nation to be forced into reliance on dozens of different translations catered to each man’s dialect, only to hear them bickering over translation supremacy; neither did Ezra want to spend the remainder of his days listening to two blind men attempt to describe an elephant.

Should believers conform their thinking and culture to the Scriptures, or should the Scriptures be conformed to the people to accommodate their thinking and cultures? Clearly, both imperative statements and narratives in both Hebrew and Greek canons underscore the problems inherent in translation. Rather than having the original language converted imperfectly to satisfy the reader’s ignorance, dialect, experiences, and appetites, the preferred approach—even in Bible translations demonstrating strong dispensational biases—is for people to convert themselves to understand the original divinely inspired language, lest they mistake their inferior and imperfect translations for the complete and perfect truth.

Translation Dependency

Since the time of Shakespeare, the English idiom “it’s all Greek to me” has been used to describe nearly anything which is not readily understandable. While on one hand the expression is useful for confessing personal ignorance, on the other hand, depending on context and vocal inflection, the expression might also express helplessness, condone apathy, or profess a crippling attitude. Not only might it say, “I don’t know,” but it also might coincidentally suggest, “I couldn’t ever possibly know,” or possibly “I don’t care.” Given this versatility, the “it’s all Greek to me” expression becomes a convenient way to respond when confronted with ancient Bible languages.

While many religious organizations have been diligent throughout the generations in dispatching handfuls of scholars to study the ancient languages in institutions of higher learning, it is fair to say that these same organizations have been equally negligent in raising their congregants to comparable levels of proficiency. Rather than teaching the congregants how to translate and understand the texts, they rely almost exclusively on translations, interpreting and translating for the congregant on rare occasions. In so doing, they intimidate and even stifle their audience, imposing a “can’t do” attitude on them. Instead of encouraging members to explore the texts in their original languages, many religious institutions instead promote systems of dependency, whereby congregants are encouraged to attend as passive bystanders and without accountability, in this way subconsciously encouraging the masses to remain in a perpetual state of infancy. Unfortunately, the end result of such passive approaches and stifling environments is the subsistence feeding of congregants, who, as Paul put it, are “not ready for solid meat.”192 Such institutions lead congregants to believe that there exists only one cow on the entire earth from which to derive milk, thus creating a perception of artificial scarcity—only to justify astronomical milk prices in excess of market value. Accepting a mere ration of milk, believers are not introduced to the herds of cows, sheep, and goats aboard Noah’s Ark—all of which are capable of producing both milk and meat. Instead, they are taught to “kill and eat” anything.

Translation Alternatives

Today, there are numerous alternatives to Bible translations and interpretations; but they are seldom, if ever, made available or promoted by status quo religious institutions via weekly service schedules or academic curriculums. Most church services and programs do not offer biblical language study programs, and the same can be said of grade school and high school curriculums—even among private schools run by religious institutions. Congregants are given church catechisms in the place of concordances, directed to constitutions instead of language lexicons, and memorize English doctrines and creeds over ancient texts.

By the time the average American Christian student completes high school, that student might have attended in excess of 20,000 hours of school curriculum, along with 750 hours of church services. To put this in perspective, it would take that student just three new words per day over the course of their curriculum to learn every word in the entire Hebrew Bible.

Young students are taught that things like art, science, geometry, math, penmanship, social studies, history, music, home economics, English, and religious doctrine are important. Yet by means of omission, students are inherently also taught that understanding God’s word in original biblical languages is far less important than all other fields of study, and this during the time they are at their prime potential for language absorption and acclimation.

Though biblical language study tools are available for free in this information age, it remains inevitable that individuals, families, and institutions will remain unable to reason beyond translations until they make it a priority to employ such resources. Until knowledge is pursued, it cannot be attained. Thus, as long as religious institutions continue to remain indifferent towards ancient language education, the only true alternatives to imperfect translations will be individual time and commitment. However, such investment in knowledge promises to return something priceless—both in this world and the next.

Translating Ignorance into Consequences

While agnostics might hope that ignorance of the truth will somehow cover a multitude of sins, Scripture testifies to the contrary. In fact, ignorance is said to be a precursor to destruction. Speaking on God’s behalf, the prophet Hosea said of Israel,

My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge... (Hos 4:6a).

Hosea wasn’t speaking simply about a lack of a conventional education—or about ignorance of a particular church doctrine. Instead, he was speaking specifically about God’s Torah, and the deliberate rejection of knowledge. Hosea continued,

...because you have rejected knowledge, I also reject you as my priests; because you have ignored the Torah of your Elohim, I also will ignore your children” (Hos 4:6b).

Although Hosea did not itemize a litany of dietary Torah transgressions as he rebuked the Israelites over two thousand years ago, it would seem that the principles of his prophecies remain directly transferrable to this generation. After all, youth today are students of algebra, chemistry, calculus, and even biology—yet they don’t know even know how many cows were aboard Noah’s ark. They are not told the first thing about defining food according to the Bible, specifically as it has been outlined in Moses’ Torah. They fail to understand how failure to observe these laws might have consequences, even resulting in their own demise. People are destroyed by eating unclean and defiled food in complete ignorance!

Translating Science into Knowledge

Centuries ago, before science became synonymous with natural philosophy, and before the scientific method became the predominant approach to the study of the natural world, the term science was used in a larger and more comprehensive sense. The word science was derived from a Latin term, which more generically means knowledge. Thus Hosea’s famous prophetic claim might just as legitimately read,

“My people are destroyed for lack of science.”

Science isn’t the only term that has assumed a different meaning since the King James Bible was first distributed. The animal types that the Bible refers to as “unclean,” science might refer to today as “biohazards.” It is for this reason that the “unclean” animal varieties, consisting of scavengers, carnivores, and omnivores, are not qualified as “food” for people according to Bible texts. For good reason, Elohim forbade the Israelites to eat unclean things such as clams, crabs, mussels, oysters, scallops, lobsters, shrimp, squid, octopus, eels, sharks, catfish, camels, rodents, rabbits, horses, pigs, boars, bears, dogs, cats, frogs, reptiles, worms, beetles, flies, or scavenging birds of prey.

Although the extent of Moses’ knowledge in the field of biology is unknown, Elohim knew by design that these same “unclean” animals host or accumulate a variety of harmful parasites, bacteria, biotoxins, carcinogens, and viruses, based largely on their diets. The list of biohazards transmitted by unclean animals includes parasitic worms like anisakiasis, gnathostomiasis, hookworms, nybelinia surmenicola, pinworms, roundworms, taenia solium (i.e., pork tapeworm), and trichinosis or trichinellosis;193 bacteria such as cholera, E. coli, listeria monocytogenes, salmonella, staphylococcus aureus, vibrio cholerae, vibrio parahaemolyticus, yersinia enterocolitica;194 biotoxins such as Amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP), Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP), and Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP);195 carcinogens like DDT, PCB’s, and heavy metals;196 or viruses like Hepatitis A, Hepatitis E, or the Norwalk virus.197 Knowing what might reside in the blood of unclean animals, Elohim not only told people to abstain from eating these things—he even directed them to avoid touching the carcasses of such animals, understanding it to be a health hazard, both private and communicable, and thus a “sin.”198

Long before the Center for Disease Control (CDC) was formed and various research on unclean foods was published, Elohim understood the diseases and various consequences associated with eating unclean things. He knew that eating substances and microorganisms contained within unclean animals could result in short term problems like abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, temperature reversal, headaches, excess tiredness, lack of appetite, dizziness, disorientation, floating sensations, numbness, or tingling in the mouth, arms, and legs. He understood that eating unclean foods might even result in symptoms such as loss of coordination, permanent short-term memory loss, focal weakness or paralysis, vision loss, blindness, muscle paralysis, seizures, adult onset epilepsy, respiratory failure, severe nerve pain, paralysis, decreased consciousness, comas, and even death.

Dispensational Translation Rejection

In rejecting God’s dietary commandments as given through Moses, dispensational theologians not only reject the goodness of Elohim as a Torah giver, but they propagate unholy and unkosher Bible doctrines through misinterpretations and mistranslations, demonstrating a gross lack of knowledge. They promote a backward theology where white is black and black is white, and where right is wrong and wrong is right. They propose that Yeshua avoided unclean animals—as described by Moses—strictly for purposes of religious ceremony, short term messianic obligation, or for the sake of manmade traditions. They insist that the dietary Torah is “done away with,” encouraging others to share in the sin of Adam and Eve. They eat foods forbidden by Moses, not acknowledging that sin is defined by the Torah and that “the wages of sin is death.”199

Equipped with the knowledge of Scripture in its full contexts and original languages, no honest or reasonable scientifically-minded 21st century individual with a simple understanding of biological life would conclude that Yeshua came to earth two thousand years ago to expel all parasites and biohazards from the entire planet. Yeshua didn’t convert non-food animals into food—either by messianic miracle or by authoritative proclamation. There is no biblical or other historical record describing how the various biohazards of Yeshua’ time either transformed or vanished before, during, or after his crucifixion. Yeshua did not, and would not, dine on dispensational doctrines or translations; he would reject them as unclean.

Translating Commandments into Love

On the contrary, Yeshua’ diet, as defined by Elohim through Moses, makes perfect sense from both a biblical and a scientific standpoint. By pairing simple science with a moral reverence for life, it becomes obvious why Moses discouraged even physical contact with biohazard-carrying animal carcasses, why Daniel would not share his kitchen with abominable creatures, and why Peter would not put any defiled food on his tablecloth or bring any unclean food to his lips. Likewise, Paul would not eat unclean creatures if they were served to him at an unbeliever’s house; and if they were placed before him, he would indeed raise questions of conscience. He would respond like Peter and Ezekiel; he would consider them to be unclean in and of themselves, irrespective of pagan temple or idol proximity. Elohim reminded Noah to eat clean foods as he disembarked from the Ark, just as he blessed Adam and Eve with the same dominion and diet back in the Garden of Eden.

It is more than the least of all human commandments to EAT LIKE JESUS; it is among the first of all human commandments. It is an act of obedience. It is a path to self-preservation, and it is a way to keep one’s neighbor from harm. It is an act of love to treat the body like a temple of the Holy Spirit and to guard it from debilitating disease.

Beyond Dietary Translations

With respect to religious reform, EAT LIKE JESUS might be likened to the tip of an iceberg. Apart from a few simple food-related doctrines, what other great truths lurk beneath the surface of other religious traditions and dispensational dogmas? What if Christians wholeheartedly revered God’s other commandments given through Moses, as Yeshua did? What if believers began to see Moses’ Torah as a gift of love from Elohim, rather than as an expression of God’s curse? What would the rest of the Bible look like if translated into English with a kosher view instead of a dispensational one? What other knowledge do the original Bible texts contain beneath the translators’ many assumptions and interpretations?

What would it look like, if the Christian church set aside dispensational dogma, religious traditions, and secondhand translations, returning to Kosher Christianity in every aspect of life? How might it affect other fields of study and occupations, such as agriculture, medicine, hygiene, government, Torah enforcement, economics, commerce, real estate, education, or family life? What about Christian doctrines—such as salvation, grace, repentance, forgiveness, redemption, atonement, sacrifice, communion, or baptism? What would these things look like apart from the dogma, traditions, and mistranslations? How do they shape religious thought and what effects might they have on individual behavior or society as a whole?

These questions are left for the reader’s consideration and investigation—or perhaps another book.

“Come now, let us reason together,” says Yehovah. “Though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they are red as crimson, they shall be like wool.” (Isa. 1:18)