Written by Nehemia Gordon

Shavuot

is a biblical festival known in English as the Feast of Weeks or Pentecost. Shavuot is a pilgrimage-feast, in Hebrew

chag

. As a

chag

, Shavuot is one of the three annual biblical festivals on which every male Israelite is commanded to make a pilgrimage to the Temple. Shavuot is also referred to in the Torah as

Chag Ha-Katzir

, the Feast of Harvest (Exodus 23:16) and

Yom Ha-Bikurim

, the Day of Firstfruits (Numbers 28:26).

The Hebrew Bible does not associate any historical event with Shavuot, although in later times it was connected with the Revelation at Sinai. The Book of Exodus says that the Revelation at Sinai took place shortly after the Israelites arrived in the Sinai Desert some time in the beginning of the Third Hebrew Month (Exodus 19:1). Like Shavuot, the exact date of the Revelation of Sinai is not specified, and it is tempting to connect the two.

Shavuot is unique among the biblical festivals in that it is not given a fixed calendar date. Instead, we are commanded to celebrate it at the end of a 50-day period known today as the Counting of the Omer. The commencement of this 50-day period was marked in Temple times by the bringing of the Omer offering and ended on the 50th day with the festival of Shavuot, as described in the Book of Leviticus:

“And you shall count from the morrow of the Sabbath from the day you bring the Omer [sheaf] of waving; seven complete Sabbaths shall you count... until the morrow of the seventh Sabbath shall you count fifty days... and you shall proclaim on this very day, it shall be a holy convocation for you.” (Leviticus 23:15-16,21).

In late Second Temple times there was a famous debate between three different Jewish factions about the meaning of the Hebrew phrase “morrow of the Sabbath” and hence about the timing of Shavuot. All three factions agreed that the “morrow of the Sabbath” was associated with the Feast of Unleavened Bread, although the precise connection led to the festival being observed on different days. The seven-day Feast of Unleavened Bread runs from the 15th day to the 21st day of the First Hebrew Month (Nissan) and marks the Exodus from Egypt, as well as the beginning of the barley harvest in Israel. All three factions connected the “morrow of the Sabbath” with the Feast of Unleavened Bread, but differed as to the exact timing and connection. The three factions who argued over the timing of Shavuot were the Pharisees who wrote the Mishnah and the Talmud, the Essenes who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Sadducees who made up the Temple Priesthood.

The Pharisees argued that Shavuot is to be counted from the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which they designated a “Sabbath.” According to the Pharisees, “morrow of the Sabbath” means the “morrow of the 1st day of Unleavened Bread.” The ancient Pharisees and their modern day successor the Orthodox rabbis begin the 50-day count to Shavuot on the second day of Unleavened Bread, which is always the 16th day of the First Hebrew Month. As a result, the Pharisee Shavuot always fell out in ancient times from the 5th to the 7th day of the Third Hebrew Month (Sivan). After the destruction of the Temple, the Pharisees became the predominant surviving faction among the Jewish leadership and their interpretation is followed by most Jews until this very day. In 359 CE, the Pharisee leader Hillel II established a pre-calculated calendar and ever since the Pharisee Shavuot has always been observed on the 6th of Sivan.

The Essenes who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls began the 50-day count to Shavuot on a different Sabbath from the Pharisees. In their reckoning, the Omer offering was to be brought on the morrow of the weekly Sabbath, in modern terms: “Sunday.” The Essenes began their count on the Sunday

after

the seven-days of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. As a result, they always began their count on the 26th day of the First Hebrew Month. The Essenes had a 364-day solar calendar, which began every year on a Wednesday and had fixed lengths for each month. Based on the Essene calendar, Shavuot always fell out on the 15th day of the Third Hebrew Month. The Essenes are presumed to have been wiped out when the Romans invaded Judea in 66-74 CE and only their documents survive today.

The third faction, the Sadducees, agreed with the Essenes that Shavuot must be counted from a weekly Sabbath, but disagreed as to which one. The Sadducees believed the 50-day count must begin on the weekly Sabbath that falls out

during

the seven-days of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. According to their reckoning, the counting towards Shavuot could begin anywhere from the 15th to the 21st day of the month, depending on what day of the week the Feast of Unleavened Bread began. If Unleavened Bread began on a Sunday, the count would begin on the 15th day of the month. If Unleavened Bread began on a Saturday, the count would begin on the 16th day of the month, and so on. Based on this counting, Shavuot could fall out from the 4th to the 12th of the Third Hebrew Month. Karaite Jews have accepted the Sadducee reckoning as the only one to be consistent with the plain meaning of the biblical text.

The Sadducees and Essenes agreed that the 50-day count to Shavuot had to always begin on the morrow of a weekly Sabbath. They only differed as to whether this referred to the Sunday during the Feast of Unleavened Bread or the Sunday following the Feast of Unleavened Bread. In contrast, the Pharisees believed the 50-day count must begin with an annual “Sabbath,” rather than a weekly Sabbath. According to the Torah, work is forbidden on the 1st day and the 7th day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. The Pharisees began their count from the morrow of the 1st day of Unleavened Bread. Although work is forbidden on this day, it is never referred to in the Hebrew Bible as a “Sabbath.” The only annual feast day to ever be referred to in the Hebrew Bible as a Sabbath is the Day of Atonement, on the Tenth day of the Seventh Hebrew Month. Work is forbidden on six other annual feast days, but the days are never referred to in the Tanakh as Sabbaths.

The bigger problem with the Pharisee interpretation of “Sabbath” is when it comes to the end of the 50-day count. Leviticus 23:16 says,

“Until the morrow of the seventh Sabbath shall you count fifty days.”

The 1st day day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread could theoretically be called “Sabbath,” even though the Hebrew Bible never uses this terminology. However, the 49th day of the Pharisee counting is not a Sabbath, unless it happens to fall out on a weekly Sabbath - the 7th day of the week. Consequently, the Pharisee Shavuot is rarely the “morrow of the Seventh Sabbath” as required by Leviticus 23:16. About once every seven years, the Pharisee Shavuot does happen to fall out on the “morrow of the seventh Sabbath.” For example, in the year 2018 the Feast of Unleavened Bread begins in the Pharisee reckoning at sunset on Friday March 30. In that year, the Pharisee counting begins on Sunday April 1, 2018 and ends 50 days later on the “morrow of the seventh Sabbath,” Sunday May 20, 2018. However, this is the exception to the rule. In most years, Shavuot according to the Pharisee reckoning is actually the morrow of seventh Monday, the morrow of seventh Tuesday, etc. The only way for Shavuot to consistently be the “morrow of the seventh Sabbath” is for the counting to begin on the morrow of a weekly Sabbath, in modern terms on a “Sunday.” Of course, Scripture did not call this a “Sunday,” because that term did not exist in ancient Hebrew. The ancient Hebrew term for Sunday morning is “morrow of the Sabbath.”

An important verse that confirms the timing of Shavuot appears in the Book of Joshua:

“And they ate of the produce of the land on the morrow of the Passover, unleavened and parched grain on this very day. And the Manna ceased on the morrow when they ate of the produce of the land...” -Joshua 5:11

This verse describes the events surrounding the cessation of the Manna, shortly after the Children of Israel entered the Land of Canaan. To understand this the significance of this verse, we must go back to the Book of the Leviticus, where the Israelites were forbidden to eat of the new crops of the Land of Israel until the day of the Omer offering:

"And bread and parched grain and ripe grain you shall not eat until this very day, until you bring the sacrifice of your God; it shall be an eternal statute for your generations in all your habitations." Leviticus 23:14

When Joshua 5:11 describes the eating of “unleavened bread and parched grain... on this very day" it is using almost the precise wording of Leviticus 23:14 “and bread and parched grain... you will not eat until this very day.” The new produce of the land was forbidden until the Omer offering was brought. Joshua 5:11 is saying that when the Israelites entered the Land for the first time, they observed this commandment and waited until the terms of Leviticus 23:14 were fulfilled. In other words, they waited for the Omer offering before eating the grain of Israel. This has been widely recognized by Jewish Bible commentators throughout history, such as the 11th Century rabbi Rashi who explains on Joshua 5:11, “morrow of the Passover is the day of the waving of the

omer

.”

Joshua 5:11 is saying that the first Omer offering in the Land of Israel was brought on the “morrow of the Passover.” Immediately after this, the Children of Israel were permitted to eat of the new crops of the Land. For the first time, the Israelites pulled out their sickles and ate of the good bounty of their new homeland.

To understand the phrase “morrow of the Passover” we need to define two terms: “morrow” and “Passover.” The Hebrew word for “morrow” is

mi-mocharat

which refers to “the morning after.” In the phrase “morrow of the Sabbath” it describes Sunday morning, the morning after the 24-hour Sabbath.

Today we commonly refer to the Feast of Unleavened Bread as “Passover.” However, in the Hebrew Bible, the term “Passover” (

Pesach

) always refers to the Pascal sacrifice. The “morrow of the Passover” is the morning after the Passover sacrifice. The sacrifice was slaughtered at twilight at the end of the 14th day of the First Hebrew Month (Nissan) and eaten on the evening that began the 15th day of the First Hebrew Month (see Exodus 12:18; Deuteronomy 16:4). The morrow of the Passover is therefore the morning of the 15th day of the First Hebrew Month.

Confirmation of the meaning of the phrase “morrow of the Passover” can be found in a verse in the Book of Numbers:

“And they traveled from Ramesses in the first month on the fifteenth of the month; on the morrow of the Passover the Children of Israel went out with a high hand in the eyes of all Egypt.” - Numbers 33:3

This verse describes the day of the Exodus from Egypt as both the 15th of the First Hebrew Month and as the “morrow of the Passover.”

What all this means is that the first Omer offering in Israel took place on the 15th day of the First Hebrew Month. The first year that the Israelites entered Canaan, the 14th of the First Hebrew Month must have fallen out on a Sabbath so that the 15th of that month was a Sunday. In that year, the “morrow of the Passover” happened to also be the “morrow of the Sabbath,” what we call “Sunday morning.” This proves the Pharisee interpretation of Leviticus 23:15 to be wrong. According to the Pharisees, the Omer offering could only be brought on the morning of the 16th of the First Hebrew Month, but in the year that the Israelites entered Canaan, they brought the sacrifice one day earlier.

The great 12th Century rabbinical Bible commentator Ibn Ezra mentions a “Roman sage” who brought Joshua 5:11 as proof for the Pharisee interpretation. According to this Roman rabbi, Joshua 5:11 is no less than the silver bullet, the irrefutable proof for the Pharisee position. This Roman rabbi argued that since Passover begins on the 15th of the First Hebrew Month (Nissan), the “morrow of the Passover” must be the 16th. This is exactly when the Pharisees believe the Omer offering is supposed to be brought, on the 16th of the First Hebrew Month. If the Israelites brought the Omer on the 16th day of the First Hebrew Month in the year they entered the Land of Israel, argues the Roman rabbi, it proves that the Pharisees are correct in beginning the 50-day count to Shavuot on the 16th.

According to Ibn Ezra, bringing up Joshua 5:11 was a disaster for the Pharisee position:

“[The Roman Rabbi] did not know that it cost him his life, for the Passover is on the fourteenth and its morrow is the fifteenth, and so it is written, “And they traveled from Ramesses in the first month, etc.” (Numbers 33:3). Eating parched grain is forbidden until the waving of the Omer.”

Desperate to salvage the situation, Ibn Ezra proposes a novel re-interpretation of Joshua 5:11. Previous rabbis understood this verse to describe the Israelites eating the new grain of the Land of Israel, which only becomes permissible each year after the Omer offering is brought (Leviticus 23:14). The time between harvest and the Omer offering might be anywhere for a few hours to a couple of weeks. During this interim period, the new grain must be stored and only old grain may be eaten, that is, grain from a previous year’s harvest. Since the Israelites were new in the Land of Israel, they did not have any grain from previous years. They had been wandering in the desert eating Manna for 40 years. As soon as they entered the Land, they harvested the grain they found growing in the fields of Jericho. They then waved the Omer, the first sheaf of the harvest, making all their new harvest permissible to eat and began the 50-day count to Shavuot.

From Ibn Ezra’s perspective, the Israelites did this one day too early, on the morning of the 15th day of the First Hebrew Month. According to the Pharisees, the Omer must always be brought on the 16th day of the First Hebrew Month. Ibn Ezra’s ingenious solution to this embarrassing biblical fact of history is to add the word “old” to Joshua 5:11. If the Israelites ate “old grain,” that is, grain harvested in a previous year, then the verse has nothing to do with the Omer offering or the 50-day count to Shavuot.

Ibn Ezra’s new interpretation was highly influential, more than most people realize. When Christian scholars started translating the Bible into English, they went to Jewish rabbis to learn the Hebrew language. When it came to Joshua 5:11, the rabbis told the Christian translators to add the word “old” to the verse. More precisely, they told them that the word “grain,” in Hebrew

avur

, actually means “old grain.” As a result, Ibn Ezra’s novel interpretation is reflected in the most famous English translation of all time, the King James Version:

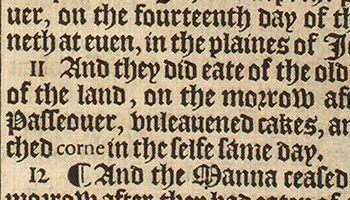

And they did eat of the old corn of the land on the morrow after the passover, unleavened cakes, and parched corn in the selfsame day. Joshua 5:11 –King James Version

(A scan of the original 1611 King James Version)

Most translations do not employ the Ibn Ezra translation trick of adding the word “old.” This is true for both Christian and Jewish translations. Here are a few examples:

“On the day after the passover, on that very day, they ate the produce of the land, unleavened cakes and parched grain.” New Revised Standard Version

The day after the Passover, that very day, they ate some of the produce of the land: unleavened bread and roasted grain.” New International Version

“And they did eat of the produce of the land on the morrow after the passover, unleavened cakes and parched corn, in the selfsame day.” Jewish Publication Society 1917

“On the day after the passover offering, on that very day, they ate of the produce of the country, unleavened bread and parched grain.” Jewish Publication Society 1985

“And they ate of the grain of the land on the morrow of the Passover, unleavened cakes and parched grain on this very day.” Judaica Press

These translations were made by people who read Hebrew and they knew that the word “old” was simply not there. The Christian translators of the King James Version, on the other hand, did not know this and took someone else’s word for it.

Ibn Ezra himself must have known that adding “old” to the verse was not the correct linguistic interpretation. In his introduction to his commentary on the Torah, Ibn Ezra declares that the rules of language and grammar must be bent to fit rabbinical interpretation when it affects practical religious observance. Adding the word “old” to Joshua 5:11 is a clear example of bending the rules of the language. Ibn Ezra reveals his true understanding when he points out in response to the Roman rabbi, “Eating parched grain is forbidden until the waving of the Omer.” He only mentions the “parched grain” from Joshua 5:11 and not the “unleavened bread” because he knows it disproves the very thing the Pharisees wanted to prove.

“Parched grain,” in Hebrew

kali

, refers to nearly ripe grain that is still slightly moist. The farmers would harvest this moist grain early and parch it in fire to make it crunchy and delicious. Parched grain could only come from a freshly harvested crop, not from old grain! Joshua 5:11 says the Israelites ate “parched grain” on the morrow of the Passover, on the morning of the 15th day of the First Hebrew Month. The “unleavened bread” could theoretically have come from the old grain, as Ibn Ezra suggested, but the parched grain had to be new grain. Year-old moist grain would go bad, so parched grain could only be “new” grain from that year’s harvest. This new crop would be forbidden to eat until the waving of the Omer, which took place on the “morrow of the Passover,” which Ibn Ezra knew from Numbers 33:3 was the morning of the 15th day of the month. That first year in the Land of Israel, the Israelites ate the new grain and began the 50-day count to Shavuot on the 15th of the First Hebrew Month. This was one day too early for the rabbinical reckoning, which is why Ibn Ezra says that bringing Joshua 5:11 into the discussion of the timing of Shavuot cost the Roman rabbi his life - figuratively speaking, of course.

One technical point to consider is that the word “morrow” is the operative term in the phrase the “morrow of the Sabbath.” Joshua 5:11 makes it clear that the “morrow” has to be during the seven days of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. The Sabbath itself might actually precede these seven days, as it did that first year the Israelites entered the Land of Israel.

In ancient times, the Pharisee Shavuot would coincide with the Biblical Shavuot about once every seven years. This would happen whenever the First Hebrew Month began with the sighting of the new moon on a Friday night. In years such as these, the 16th day of the month would be both the second day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread and the morrow of the weekly Shabbat. The modern rabbinical calendar established by Hillel II in 359 CE calculates the beginning of the month using the dark moon, making this a less common scenario.